Save 50% on a 3-month Digiday+ membership. Ends Dec 5.

Domain spoofing remains an unsolved issue in programmatic advertising

Ask marketers about a persistent, unresolved issue in programmatic advertising, and many will agree: domain spoofing.

Domain spoofing, where unscrupulous publishers, ad networks or exchanges obscure the nature of their traffic to resemble legitimate websites, is not a new problem in the industry. But it has gained much attention lately because marketers are increasingly focused on fraud and brand safety.

The Interactive Advertising Bureau Tech Lab, for instance, started an initiative called ads.txt last month to show media buyers eligible distributors of a publisher’s inventory. For example, if a demand-side platform or an agency trade desk wants to buy inventory from goodsite.com on an open exchange, it will be able to see if that exchange is an authorized reseller of the publisher by visiting http://goodsite.com/ads.txt.

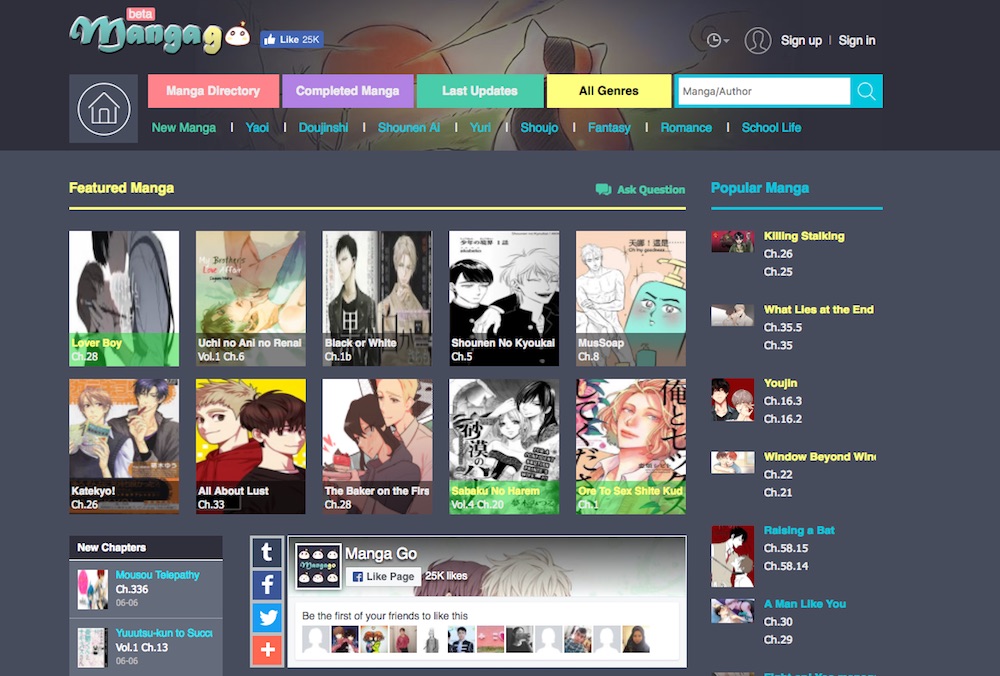

Spoofed domains are not just fake website addresses, they are also banner farms that contain bad content, according to programmatic analytics firm Metamarkets. For instance, the company has a brand client whose ads should have been served to a legitimate entertainment website with very high monthly traffic. But the brand’s ads ended up instead on an unknown site called mangago.me.

Domain spoofing is not only caused by ad networks, exchanges or fraudulent websites. At least 10 out of the top 100 publishers ranked by comScore are also feeding this practice by buying fraudulent traffic from ad networks, according to Chris Wexler, svp and executive director of media and analytics for agency Cramer-Krasselt. “Those fraudsters get a few cents more per thousand [impressions] today, but in the long run, it depresses revenue for legitimate publishers and trust in the market for advertisers,” said Wexler.

The flow of an ad impression is typically like this: A publisher creates a bid request, passes it to several supply-side platforms or ad exchanges that further send the bid request to multiple DSPs. Once the bid is won, the publisher ad server will call the demand side ad server and the ad is rendered, according to Mike Caprio, chief growth officer for ad tech firm Sizmek.

Ad position: web_incontent_pos1

“None of those parties have full visibility on what happens as it takes a number of hops in the process,” said Caprio.

A bid request itself contains information like a publisher’s domain, article URL, ad placement ID and other metadata like content category and user information. It is hard for DSPs to catch fake domains because they make transactions mainly based on the site domain and article URL in bid requests. If a publisher, an ad network or an ad exchange rewrites the domain in the first place, DSPs won’t be able to tell the difference, according to Curt Larson, vp of product for programmatic native firm Sharethrough.

Theoretically, SSPs are the first line of defense and should be checking things like the origin of the page and when the domain registration took place (if a site was registered two days ago, there’s no way it can sell 50 million impressions in an open exchange, for instance), but SSPs have no incentive to do so because they make money off the volume they push through, according to Caprio. And SSPs that are in the practice of aggregation could spoof the domain from a small site and sell it as if it were on a more well-known domain, added Steve Sullivan, vp of partner success for Index Exchange.

And for agencies, finger pointing among ad tech middlemen makes it even harder to catch nefarious behaviors. “The opacity of the impression supply and distribution chain makes it easy for everyone in the chain to push responsibility to someone else,” said Wexler. “The truth is solving [domain spoofing] is very hard and expensive. Everyone is hoping someone else is going to do it so they don’t have to spend their time and effort.”

Dan Davies, svp and director of media sciences for agency MullenLowe’s Mediahub, also said that he experiences vendors’ finger pointing a lot. His team works with third-party companies like Moat and Integral Ad Science to check if an impression’s domain information and page information match, but nobody can catch spoofed domains completely.

Ad position: web_incontent_pos2

“I think ad exchanges are in the best position to filter sellers,” said Davies. “I really hope that the industry can crack down on domain spoofing. As we clean up more and more ad inventory the CPM will probably go up, but that’s fine as long as we are buying legitimate impressions.”

While media buyers can work with third-party vendors to run pre-bid and post-buy verification, the technology for DSPs and SSPs to detect spoofed domains in real time doesn’t exist today, according to executives interviewed for this article. Both Larson and Sullivan hope that the IAB’s ads.txt project can bring more transparency to programmatic because this initiative urges SSPs to be diligent about only representing media that they are authorized to sell.

“The sell-side of the industry must take responsibility for this issue,” said Sullivan. “On the other hand, DSPs must not turn a blind eye to those opportunities that seem too good to be true.”

More in Marketing

Ulta, Best Buy and Adidas dominate AI holiday shopping mentions

The brands that are seeing the biggest boost from this shift in consumer behavior are some of the biggest retailers.

U.K. retailer Boots leads brand efforts to invest in ad creative’s data layer

For media dollars to make an impact, brands need ad creative that actually hits. More CMOs are investing in pre- and post-flight measurement.

Ad position: web_bfu