Save 50% on a 3-month Digiday+ membership. Ends Dec 5.

Why Time, Conde Nast and other magazine publishers are charging into brand licensing

Twelve years ago, Gary Caplan took a meeting with Time Inc. to discuss pots and pans. Caplan, a brand-licensing agent from California, was in New York on behalf of Corningware to forge a deal with Real Simple, Time Inc.’s biggest lifestyle title, that would put the magazine’s logo on a line of kitchenware. It didn’t go well.

“It was like pulling teeth,” Caplan recalled. “They didn’t get it.”

It turns out Caplan tried to take that meeting about 10 years too early. After years of treating brand licensing as an afterthought, magazine publishers have embraced it as they look to replace their print advertising revenues, which are in a systemic decline and can’t be made up quickly enough by digital ad revenue.

They are finding increasingly willing participants on the other side of the negotiating table, as the years of investment that magazines have poured into digital presences, social footprints and creative studio capabilities have made them attractive partners for product manufacturers.

In the U.S. and Canada, the retail value of all the brand-licensed goods sold in 2016 totaled $272 billion worldwide. While that money is spread across a wide swath of industries, publishers are taking a big bite out of it. The biggest actor in the space is Meredith, parent of Better Homes and Gardens, which accounted for over $22 billion, up from $17 billion two years ago and second only to the $57 billion generated by Disney, according to License Global.

Other publishers that are active in licensing include Playboy, with $1.5 billion; Hearst, accounting for $350 million; Rodale, $155 million; and Condé Nast, $150 million. Those totals are largely flat year over year.

While Meredith stands head and shoulders over the rest of the publishing world, brand-licensing observers see a lot of runway for other magazine publishers. “I think it will get much bigger, especially as more of these magazines lean into becoming lifestyle brands,” said Karina Masolova, the executive editor of The Licensing Letter, which monitors brand licensing.

Ad position: web_incontent_pos1

‘Untapped potential’

Like everything in media, brand licensing isn’t new. Playboy, which owes all of its profits to brand licensing, has been slapping its rabbit ears on everything from nightclubs to cigarettes for over 60 years. All Condé Nast’s 22 brands have done at least one brand-licensing program, said chief experience officer Josh Stinchcomb, who sees “untapped potential across the board” for further programs.

But for most of the previous century, brand-licensed products took a back seat for magazine publishers. Their principal source of revenue was print advertising. Publishers carefully protected the relationships that fueled that income. And brand licensing was a threat: If a beauty magazine launches a branded makeup line, L’Oréal might not appreciate the extra competition.

Brand licensing also operated on a different timeline. Where a magazine publisher typically thinks in quarters or 12-month periods, brand licensing moves out of step with ad sales. “Magazine publishing is a very short-cycle business,” said Elise Contarsy, vp of brand licensing at Meredith. “It can take over a year to finalize a licensing agreement in terms of getting the terms down.”

‘Fundamentally reimagine’ the business

In recent years, though, with print revenues dwindling, publishers have stepped up their brand licensing. Hearst hired a new vp of brand licensing, Steve Ross, in May. National Geographic, which saw its brand-licensed products account for $360 million in retail sales in 2016, hired two executives, Rosa Zeegers and Juan Gutierrez, away from brand licensing heavyweight Mattel. Condé Nast announced an expanded brand-licensing strategy a year ago. The results have already included Glamour-Lane Bryant clothing line, cookware from Epicurious and swim trunks for GQ.

Ad position: web_incontent_pos2

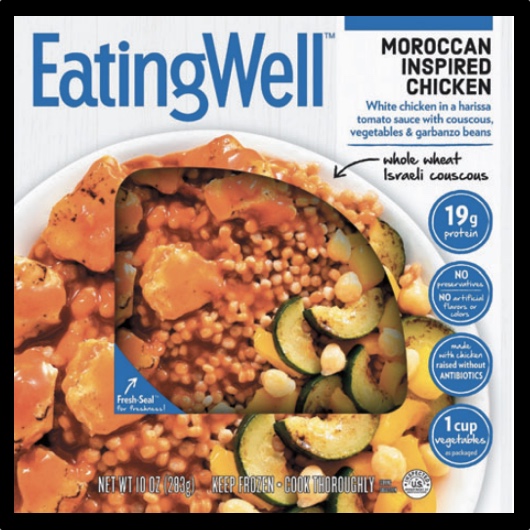

Time Inc. has gone on a tear of its own, expanding existing relationships like one between Real Simple and Bed Bath & Beyond and adding new ones, resulting in Southern Living-branded read-to-eat dinners sold in grocery stores, Cooking Light-branded popcorn and Sports Illustrated-branded bikinis. “We want to fundamentally reimagine each brand across the business,” said Bruce Gersh, Time Inc.’s svp of strategy and business development.

Gersh, whom Time Inc. CEO Rich Battista hired from ITV last year, has a long history in this space. Gersh came up with the concept of Shop the Soaps, which built lines of jewelry and fragrances on the back of daytime institutions like “All My Children.” Brand licensing is a big focus of his, and he envisions similarly ambitious integrations across Time Inc.’s portfolio. It’s not clear how big a business this is for Time Inc. currently — the company does not break brand licensing out in its public earnings.

“We’ve spent the last few months with our existing clients and customers figuring out how we can reimagine this relationship,” Gersh said. “Each business needs to be reinvented.”

Manufacturers, in turn, are drawn to publishers because they’ve become more sophisticated marketers. Where 10 years ago, all a publisher had was its brand and print circulation, today they reach many more times that on social media and boast first-party data on millions of customers and retargeting skills.

“When you combine the insight we can glean from hundreds of millions of consumers, the relevance of iconic brands in our stable and the power of our distribution platforms, I like our chances in any market environment,” Stinchcomb said.

Publishers can offer creative branding and marketing services, too. Condé Nast and Time Inc. have used their social followings as well as influencer networks to promote their licensed products. “If you look at how we support some of our licensing partners today, it’s completely different,” Contarsy said. “If one of our licensing partners is looking for content, that’s something we can do better than they can do.”

Publishers also can run ads for the products on their own platforms, at preferential rates. While publishers “can’t give away” inventory, as Contarsy put it, they can offer ad space at a friends-and-family price.

Selling points

Manufacturers need the brand familiarity and the reach those ads provide because the competition for shelf space has gotten brutal. Credit Suisse estimated that 8,000 U.S. retail locations will close this year, up from about 3,000 that closed last year. That situation means manufacturers and retail brands seeking recognition are more willing to take a chance on upstart publishers, the way Target did with Clique Media Group’s WhoWhatWear capsule collection last year.

But like any market, there are risks. It’s hard enough for Sports Illustrated to compete for advertising with ESPN. But in brand licensing, it also has to compete with all the major sports leagues, as well as those leagues’ players and their commentators.

That’s why some publishers have turned to talent agents to jumpstart their brand-licensing operations. Last June, Nylon signed a deal with an agent at United Talent Agency that has yielded some projects, including a branded subscription box.

“Unless you have built an infrastructure over years for licensing, it becomes an expensive and cluttered landscape to manage all in-house,” said Nylon president Jamie Elden, who wants to make brand licensing 30 percent of Nylon’s revenues over the next few years. “The value of those introductions and knowledge is priceless to a medium-sized media company.”

There’s no guarantee that brand licensing will grow into a large slice for all other publishers. Even today, many magazine publishers still get cold feet about forging branding deals, fearing ad partner reprisal, according to Stu Seltzer, the president of the Seltzer Licensing Group, which has executed brand licensing arrangements for companies including CBS and Unilever. And in some product categories, like housewares, it can take years before the deals forged begin to affect licensors’ balance sheets.

But publishers claim they’re ready to be patient. “These are supposed to be long-term partnerships,” said Kevin LaBonge, the executive director of global licensing at Rodale. “In a perfect world, they’re marriages.”

More in Media

What publishers are wishing for this holiday season: End AI scraping and determine AI-powered audience value

Publishers want a fair, structured, regulated AI environment and they also want to define what the next decade of audience metrics looks like.

Digiday+ Research Subscription Index 2025: Subscription strategies from Bloomberg, The New York Times, Vox and others

Digiday’s third annual Subscription Index examines and measures publishers’ subscription strategies to identify common approaches and key tactics among Bloomberg, The New York Times, Vox and others.

From lawsuits to lobbying: How publishers are fighting AI

We may be closing out 2025, but publishers aren’t retreating from the battle of AI search — some are escalating it, and they expect the fight to stretch deep into 2026.

Ad position: web_bfu