Save 50% on a 3-month Digiday+ membership. Ends Dec 5.

Sweden has just celebrated 250 years of press freedom. If you thought this tradition would make it safe from fake news, you’d be wrong.

According to Ehsan Fadakar, social media columnist at tabloid Aftonbladet, Sweden has seen a worrying growth in hate speech and sharing misinformation about immigration. Sweden has historically been a popular place for migrants. The number of asylum applications to Sweden doubled between 2014 and 2015 to more than 160,000 — as many as half were routinely accepted. However, as in Germany, immigration has fueled anger and, in turn, has given rise to nationalist groups in the country not unlike the so-called alt-right in the U.S.

Here, then, are four things to know about the state of fake news in Sweden.

Publishers have direct relationships

Sweden is a small country with a population of 10 million people, four national newspapers, and popular publicly owned TV and radio networks. With a relatively small media pool, people have a close relationship with the brands. Because of cheaper mobile data plans, early investment in apps and mobile responsive sites, it’s also more more common for people to subscribe to publishers. As such, fewer people than, say, in America are getting their news from Facebook.

According to Schibsted, parent company to tabloid Aftonbladet and daily newspaper Svenska Dagbladet, 90 percent of its online daily readers are direct traffic, to their sites or through apps. The spread of fake stories on Facebook hasn’t accelerated at the same rate as in other countries.

Trying to burst the Facebook filter bubble

Even so, policing the amount of fake news on Facebook is a mammoth task. The social network has come under fire for not doing enough itself to tackle the problem. Tools launched in the U.S. and in Germany rely on users reporting the problem. In Germany, Facebook has outsourced the solution to small third-party fact-checking organization.

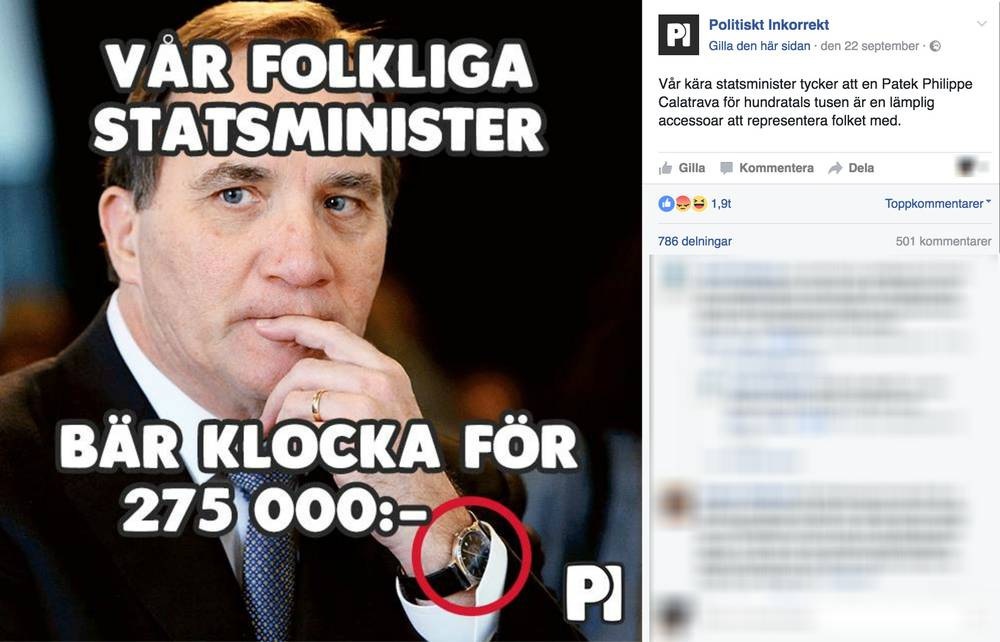

Last September, a newly launched site called Politisk Inkorrekt, whose tagline is “anything but politically correct,” ran a story that Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Löfven had an outlandishly expensive watch. On Facebook, the story gained around 1,000 shares and 2,000 reactions. After investigating, Aftonbladet found it was a gift and not worth nearly as much. The publisher then spent between 3000 and 4000 Swedish Krona ($340-$450) to amplify this story, targeting the people who had commented on the fake one.

Ad position: web_incontent_pos1

“It’s an expensive way of doing it,” said Ehsan Fadakar, social media columnist at the publisher. “But Aftonbladet is a popular Swedish publisher on Facebook. We have some responsibility to prevent people from seeing fake news.”

Further distinguishing between real and fake

Content posted to Facebook often lacks context — it’s not always clear if something is opinion, analysis or news — and publishers are thinking of ways to make real news more easily identifiable.

One Swedish daily newspaper has started posting footnotes saying opinion pieces do not reflect the views of the paper. Another, Swedish tabloid, Expressen, has been embedding two links at the bottom of each article, one asking people to submit any factual inaccuracies with the article, the other to report the article to the press regulators, the Press Ombudsman. “It’s a way for serious newspapers to be regulated on whether they have been ethical or not,” said Anna Gullberg, editor-in-chief at local newspaper publisher MittMedia. “More publishers are ready to go the same way.”

“There is some discussion that all websites meeting journalist standards should have certification,” said Thomas Eriksson, head of digital content for Egmont Publishing in Sweden. “It’s an interesting and good idea, then the reader can then immediately tell where it’s from.”

Ad position: web_incontent_pos2

Fake Facebook groups

According to Fadakar, it’s a common tactic for right-wing groups on Facebook to start pages under misleading names, like “In support of the Swedish police,” to gain followers.

“Of course, everyone is in support of the Swedish police, but when you take a look at the types of pages these groups are sharing, you can see who it’s really run by. Then they can gain up to 400,000 new followers. People may then unfollow once they find out, but people don’t like admitting their mistakes.”

More in Media

What publishers are wishing for this holiday season: End AI scraping and determine AI-powered audience value

Publishers want a fair, structured, regulated AI environment and they also want to define what the next decade of audience metrics looks like.

Digiday+ Research Subscription Index 2025: Subscription strategies from Bloomberg, The New York Times, Vox and others

Digiday’s third annual Subscription Index examines and measures publishers’ subscription strategies to identify common approaches and key tactics among Bloomberg, The New York Times, Vox and others.

From lawsuits to lobbying: How publishers are fighting AI

We may be closing out 2025, but publishers aren’t retreating from the battle of AI search — some are escalating it, and they expect the fight to stretch deep into 2026.

Ad position: web_bfu